2021/2022 Season:

| Date | Speaker | Title | Abstract |

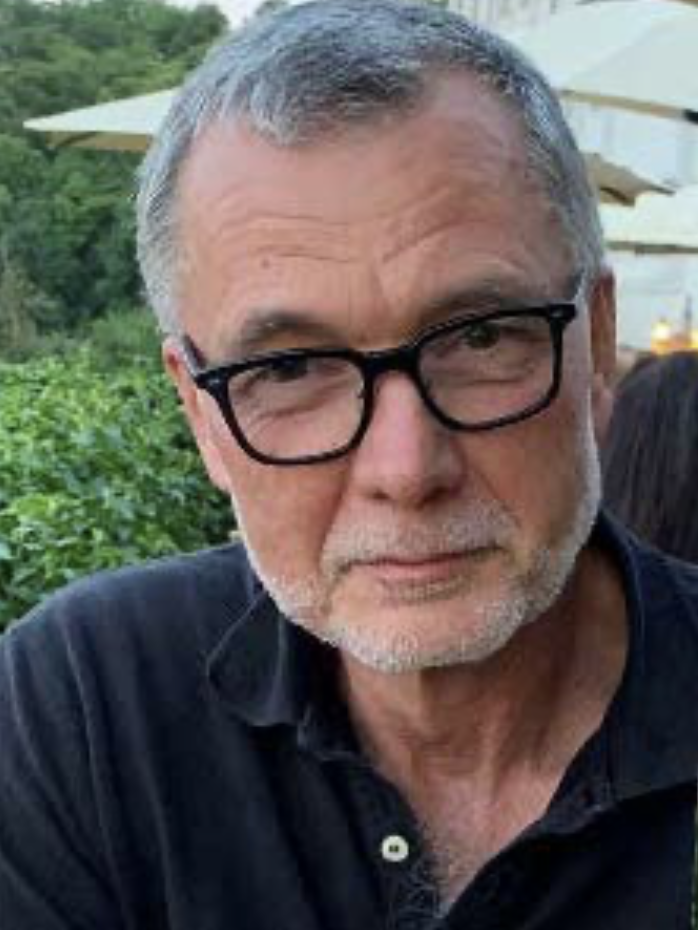

| November 2, 2021 |

Dr. H. S. Grütter, Ph D, P Geo, SRK Consulting (Canada), |

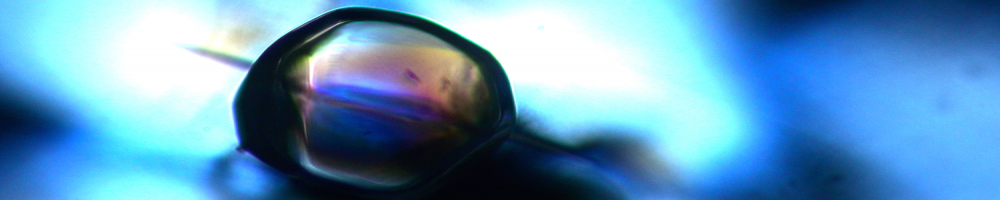

Observations on "Lows" and "Highs" in contemporary microdiamond data

|

The evaluation of advanced stage diamond projects is materially constrained by the time and cost involved in bulk sampling (or trial mining) campaigns that serve to demonstrate the grade and value of (macro)diamonds in a deposit. However, comparatively inexpensive assay data for (micro)diamonds may also be used to estimate (macro)diamond grade, by way of geostatistical extrapolation or modelling of total diamond content curves and diamond size frequency distributions. Geoscientists at SRK (Canada) Inc. compiled publicly available technical disclosure related to micro/macrodiamond sampling campaigns completed since early-2004 and developed a model-independent benchmarking approach to estimate in-situ (macro)diamond grades based on microdiamond assay results – a one-page summary of that work is available here: https://www.srk.com/en/publications/benchmarked-macrodiamond-grade-estimates-from-microdiamond-data Our ongoing investigation of microdiamond data has developed a focus on the occurrence of “low-count” and “high-count” microdiamond assay results. In this VKC talk we contrast “normal”-count with “low”-count results (Snap Lake vs FALC and others) and appeal to diamond-bearing mantle xenoliths to explain occasional “high”-count results. Real-world examples are used to cover topics like microdiamond sample sizes and (attained) resolution thresholds in the range 1 part in 1010 to 1012. The talk closes out with an examination of the microdiamond dataset for the Tuwawi pipe (northern Baffin Island). |

| November 30, 2021 |

Murray Rayner, Principal Geologist, Rio Tinto (Australia), |

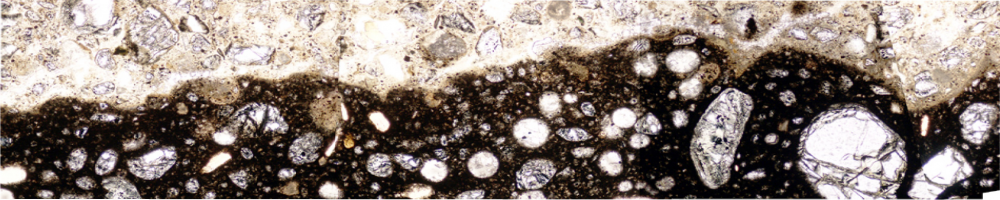

The discovery and geological history of the Argyle AK1 diamond deposit: The Argyle Diamond Mine

|

Since the discovery of world class Argyle diamond deposit in 1979 and the commencement of mining of alluvial diamonds in 1982 and the AK1 pit in 1985, the geology of the AK1 lamproite pipe has changed significantly over the years. The of the Argyle AK1 deposit mine has now ceased production since November 2020 and is currently in closure and rehabilitation. The talk will discuss the discovery history of the Argyle AK1 deposit, alluvial diamond mining, open pit and block cave mining, general diamond aspects, the evolution of the geological model and the mining of the orebody within the pit followed by the block cave. It will also describe the current emplacement model and internal lamproite domains that display iconic lamproite textures. |

| February 8, 2022 |

Dr. M. G. Kopylova, PhD, University of British Columbia |

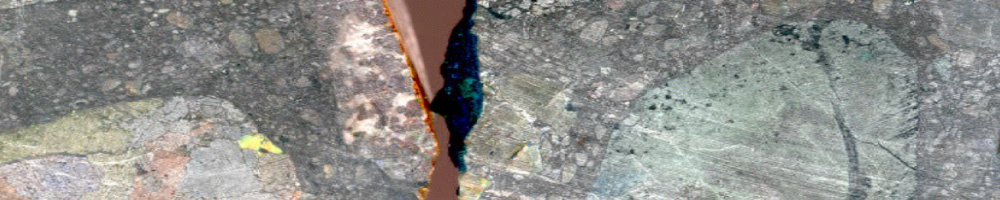

What lamprophyres teach us about kimberlites: Lessons from the Kola Alkaline Carbonatitic Province

|

Lamprophyres and related carbonatites rarely occur spatially and temporally close to kimberlites. One of these synchronous proximal kimberlitic and alkaline locations is the Archangelsk Kimberlite province (AKP) next to the Kola Alkaline Carbonatitic Province (KACP). We studied KACP lamprophyre dykes in a tight geographically defined area where rocks systematically change from carbonatite-bearing massifs on the northwest, through lamprophyres, turjaites and foidites in between, and to AKP kimberlites on the southeast. High-resolution isotope (Sr, Nd, Pb) analyses of the lamprophyres and their comparison with coeval kimberlites enabled new insights on the origin of kimberlites. I will show that the metasomatized mantle beneath the kimberlite province is necessary to generate alkaline melts, and lamprophyres may have identical melt sources with kimberlites. This poses a question of what makes one melt a kimberlite and another a lamprophyre. The presentation will give examples on how the ascent rate may control the identity of the melt in the crust. Another practical lesson from the new data on the petrography, mineralogy and isotope geochemistry of lamprophyre dykes is a recognition of a hallmark Sr-Nd trends for melts from large alkaline or kimberlite provinces. The trend of a strong positive correlation of Sr and Nd isotopic compositions at highly radiogenic (87Sr/86Sr)I results from fenitization of the old crust. |

| March 8, 2022 |

Jarek Jakubec, Dipl Ing, C Eng, FIMMM, Consultant and Leader of the Mining and Geology Group, SRK |

Mining for diamonds: History and present

|

This is an overview of historical and modern mining methods implemented in diamond mines worldwide with the focus on primary diamond deposits. Mining of primary kimberlite diamond deposits on an industrial scale had only emerged with diamond discoveries in South Africa within the second half of the 19century. Initially, kimberlite deposits were mined as open cast mines but as soon as open cast mining reached technical and economic limits, underground mining was implemented in the 1890s. To date, primary diamond deposits mined by surface or underground mining methods on an industrial scale are mainly volcanic pipes, steeply dipping dykes or shallow dipping sills. The recent discovery of tube-like shallow dipping bodies will no doubt justify consideration of different underground mining approaches. Underground mining only became practical after the development of the chambering method in the 1890s which remained in use until the 1950s, when the block caving mining method was implemented. Since then, more than 18 mining methods have been introduced and developed in diamond mines. Another major development in diamond mining is offshore mining along the coast of Namibia. Open pit mining today accounts for the majority of carats produced but underground mining is playing an increasing role. Excluding alluvial and offshore diamond mines, approximately 15 of 50 primary diamond deposits are operated as underground mines and another 15 or so have underground plans or hold the potential for underground mine development. |

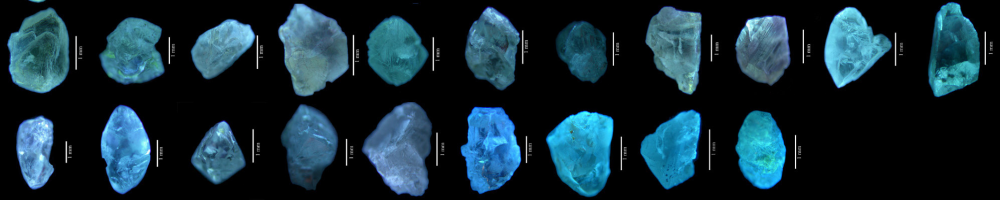

| April 13, 2022 |

Roy Bassoo, PhD, Post-Doc at the Gemological Institute of America |

Diamonds from Guyana and the Guiana Shield

|

Diamonds have been mined in Guyana for more than 130 years and are traded in major diamond centers in Belgium, Israel, and United Arab Emirates. Notwithstanding this long history, the primary source rocks of Guyana’s diamonds remain mysterious. Most of the diamonds from the Guiana Shield are likely derived from unknown rocks of the Roraima Supergroup and may include primary igneous rocks. There have been a handful of scientific studies which address Guyana’s diamonds provenance and formation, but there has not been any of detail aimed at the exploration or gemological community. I present a description of Guyana’s diamonds to serve as a comparison with other diamond populations in the Guiana Shield and elsewhere. I include details concerning color, morphology, nitrogen content, luminescence and how we may use these observations to identify primary diamonds. Diamond inclusion composition was also measured insitu and used to inform us of the cratonic root beneath the Guiana Shield. I also provide an overview of diamond mining practices and production. Being Guyanese, I grew up hearing about Guyana’s diamonds deep in the Amazon jungle, which sparked my imagination and scientific curiosity. I combine my observations and historical accounts to provide an overview of diamonds and diamond mining in Guyana. |

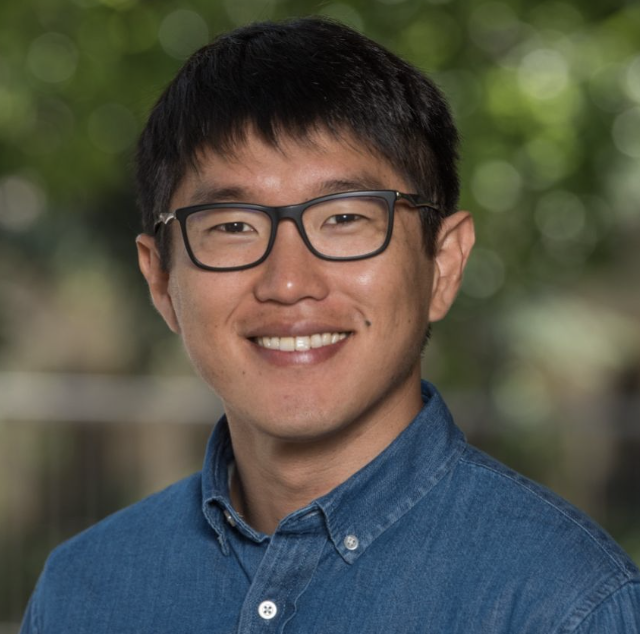

| May 11, 2022 |

Seogi Kang, PhD, Post-Doc at Stanford University |

First Successful Delineation of Kimberlite Units Using Multiple Airborne Geophysical Methods

|

DO-27 kimberlite near Lac de Gras in the central Slave Craton, NWT, Canada, is one of a few examples where airborne geophysics led to the discovery of a kimberlite body, DO-27 was a challenging target located under the lake and overlaid by the thick overburden (~50 m). Following the discovery, more airborne geophysical data including gravity and electromagnetic (EM) data have been acquired. In this presentation, I report on a new successful approach that constructs a 3D pseudo-geologic model delineating kimberlite units including volcaniclastic kimberlite (VK), hypabyssal kimberlite (HK), and pyroclastic kimberlite (PK). This new methodology was based on four physical property models including density, magnetic susceptibility, resistivity, and chargeability obtained from the multiple airborne geophysical data. Our geophysical model showed a good match to the geological model demonstrating the value of the airborne geophysical methods to delineate kimberlite units. In particular, the chargeable volumes obtained from the EM data played an important role in delineating the diamondiferous PK unit. |

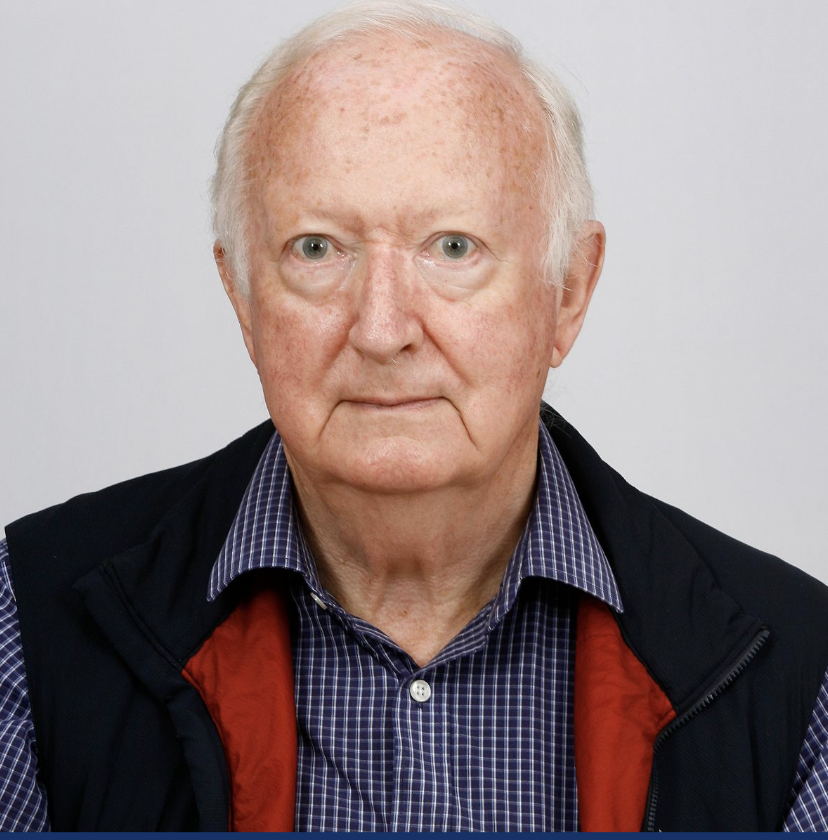

| June 23, 2022 |

Jeff Harris, PhD, University of Glasgow |

Diamond deposits of Namibia

|

This talk covers the historic and present development of the coastal alluvial diamonds found in Namibia. From the initial discoveries near Luderitz, then south to the mouth of the Orange river, with examination of the mines developed along the lower reaches of that river. |